On John Stott, Godly Ambition & History Makers

As a Christian teenager growing up in the late 1990’s, the songs of the band Delirious? were never too far away from my ears. Ok, hands up, I had more than my fair share of ‘I want to be Martin Smith‘ moments. As far as I’m concerned their first proper album, 1997’s King of Fools, is the stuff of legend. The penultimate track, History Maker, is one of their best known (as it happens, it was also re-released as their final ever single in 2010) and features the anthemic chorus lyric: “I’m gonna be a history maker in this land”.

But I remember a particular conversation a few years later that put a dampener on my perception of the song. I was talking with a friend who was a few years older than me, and he made a remark along the lines of: “You do know, it can’t be a Christian song with that lyric”. Boom. I was dumbfounded and didn’t know what to think. Over the years since, I’ve often thought about his words. Was my friend right? It quickly became less about the merits of that particular song and more about the sentiment behind the words. Is ambition really so wrong for a Christian?

And that’s where John Stott comes in. If you’re seeking to get a grip on the present state of evangelicalism in Britain today, then you probably won’t get far before you come across the name of John Stott. Named by Time magazine in 2005 as ‘One of the 100 Most Influential People in the World’, the significance of Stott’s ministry was indicated when, after his death in 2011, memorial services were held all over the Western world, as well as in cities throughout Africa, Asia and Latin America.

Stott is probably best known through his books, authoring over 50, many of which are translated into numerous languages. I remember feasting on his Bible Speaks Today ‘Romans’ commentary as an undergraduate, and then slowly making my way through the colossal The Cross of Christ over one summer holiday in Pembrokeshire.

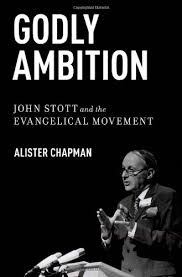

But given Stott’s prominence and impact upon evangelicalism, it is no wonder that now books are being written about him. Up until recently the stand-out was Timothy Dudley-Smith’s two-volume biography, but a couple of years ago Alister Chapman produced a more academically-focused account. Its title, ‘Godly Ambition’, as well as its emphasis, took me back to that History Maker conversation nearly ten years ago.

Interestingly the title phrase itself comes from Stott’s own pen:

“Ambitions for self may be quite modest. . . . Ambitions for God, however, if they are to be worthy, can never be modest. There is something inherently inappropriate about cherishing small ambitions for God. How can we ever be content that he should acquire just a little more honour in the world? No. Once we are clear that God is King, then we long to see him crowned with glory and honour, and accorded his true place, which is the supreme place. We become ambitious for the spread of his kingdom and righteousness everywhere.” (The Message of the Sermon on the Mount (IVP, 1993), 172–173).

Certainly to assess a Christian’s life is a strange thing. As one reviewer has pointed out, “for many, Christian lives are to be exemplary, and as such the biographer is faced with a peculiar set of expectations among potential readers.” Yet from our limited perspective it seems that God accomplished much spiritual fruit through Stott’s life and work. Chapman acknowledges this, yet he also steers away from simply being hagiographical. Weaknesses are not hidden under the carpet, and the same goes for what were arguably mistakes of judgement. Likewise Stott had a particular upbringing of privilege, and lived at a particular time, which naturally come into the assessment. Elsewhere Carl Trueman has made an important comment on the dangers of never examining critically. We respectfully give thanks for signs of God’s grace, but we also seek to learn lessons from the past. Indeed, realising someone was not perfect only magnifies God’s kindness all the more.

Yet despite the caveats I think Stott’s call to godly ambition remains a challenge. Should we not want to be part of making history? Isn’t this a matter of stewardship of our lives?

Of course, ultimately God is the only History Maker, the sovereign History Shaper, the gracious Life Giver and the humbling Life Taker. We’d be fools to lose sight of this. Solomon is quick to rebuke us when pride or self-sufficiency creep into our ambitions:“Unless the Lord builds the house, the labourers work in vain” (Psalm 127:1).

Yet under God, dependent on Him for everything, should we not seek to spend our lives ambitiously for God’s fame and glory? Should we not have a hunger to see God at work? Should we not “dream such big dreams for God, that without him they are unfeasible”? Should we not be zealous to ‘leave it all out on the court’, as we count our race’s average of ‘three score years and ten’ as an opportunity to make much of Him?

Of course it’s also very easy to think of ambition only in very quantitative terms. We might naturally think of ‘achievement’ as related to titles, jobs, and numbers through the door, etc. But God defines the realms in which we might prayerfully focus our ambition in a rather challenging way. What is my ambition for my marriage? My family? My own personal spiritual life and godliness? This is not about podiums and booksales. This is about investing in lives and relationships for the sake of the gospel. It’s about being patiently walking alongside individuals in belief and unbelief, prayerfully testifying to Jesus Christ. It’s about raising our kids. It’s about committing to love and serve each other, being generous with our time. Success is measured in faithfulness, although that does not mean we cannot be ambitious about our faithfulness being fruitful for Him.

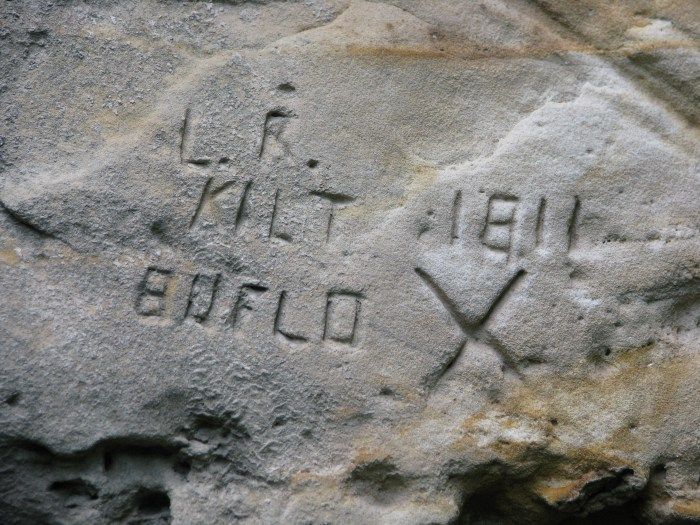

Let’s not seek to make history for the sake of our own reputations, furiously trying to scratch out our own names in the rock face of this planet. But likewise let’s not sit back and remain apathetic to the opportunities of life. Like Stott, let’s be ambitious, joyfully and sacrificially spending ourselves engraving His name, to the praise of his glorious grace. Let’s give ourselves fully to being part of His Story, one that he is weaving in and out of our little lives, using the big stuff and the mundane stuff, the hidden and the public. With the lives he gives us, long or short, let’s be history makers.

What do you think? Up for it? Or am I off-piste?

—

For more on ‘Godly Ambition’, see Nathan Finn’s review of the book for Themelios here. Below is a short interview with Chapman when he visited my seminary, Oak Hill College, a couple of years ago.