Evangelism in A Sceptical World by Sam Chan – A Review

According to author, evangelist and medical doctor, Sam Chan, we face a crisis in the Western church. It is the crisis of seemingly deaf ears: people are increasingly apathetic or hostile to the Christian faith. We present our best arguments, yet people often appear disengaged. No one seems to care anymore whether or not there’s a ‘case for Christ’. As Don Carson puts it in the foreword to this book,

“Christians who share their faith, and the people with whom they are sharing, live in different worlds… even brief conversations about religion feel a bit like two ships slipping past each other in the night, neither quite comprehending that the other is there.”

And whilst we always need to rely on the Spirit of God to regenerate hearts, how do we respond when the ways we’ve historically presented the gospel don’t seem to quite connect as they once did?

Textbook Evangelism

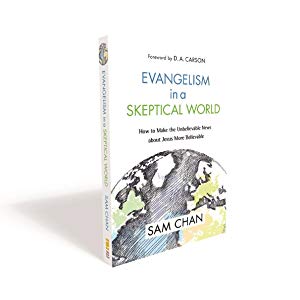

It is into this apparent predicament that Chan has written Evangelism in a Sceptical World. Scooping up Christianity Today‘s 2018 Book of the Year award in the category of Apologetics/Evangelism, it has the feel of an evangelism textbook – part theory, part method – to help the Church take some forward steps in our thinking and practice on communicating the gospel in our changing context.

But for many of us, Chan’s premise involves facing uncomfortable questions. By conviction we want to be faithful to the gospel entrusted to us – and so we are wary of changing the message in order to soothe the itching ears of the world. Yet Chan argues this can sometimes stop us doing the necessary work of evaluating our methods of communication – and more than that, evaluating the way we’re framing the gospel itself. As he says,

If we don’t use the language, idioms and metaphors of a person’s culture, then our message will be meaningless. But if we do use the language, idioms and metaphors of the person’s culture, we may be understood, but we also risk syncretism with their culture. I believe this is a risk work taking.

Naturally some will be more hesitant about Chan’s posture than others. But he argues that to avoid these questions by all too quickly defaulting to an approach of ‘just give them the gospel’ is a failure to recognise and own the communicative and theological decisions we’re already making. As he says, evangelism is “an event where the gospel is communicated,” but “there is no single method of communicating the gospel”.

Resonate, Dismantle, Complete

In many ways, Chan is arguing that we can communicate more effectively by working harder to show how the gospel existentially resonates with our listeners. As an Australian Asian who was born in Hong Kong, studied in the US, and now lives and ministers in Australia, Chan adeptly analyses the ‘storylines’ of these cultures and demonstrates how these shape how he might present the gospel. He uses the language of ‘points of entry’, arguing that in God’s common grace, people have God-given, legitimate, existential cries: “let’s hear these cries. Let’s understand the storyline and show that we empathise with it. Then let’s show them how Jesus is who have been looking for.” That’s not to say that we change the gospel, nor its necessary response of repentance and faith, but rather that we need to think through how this gospel connects with our listeners.

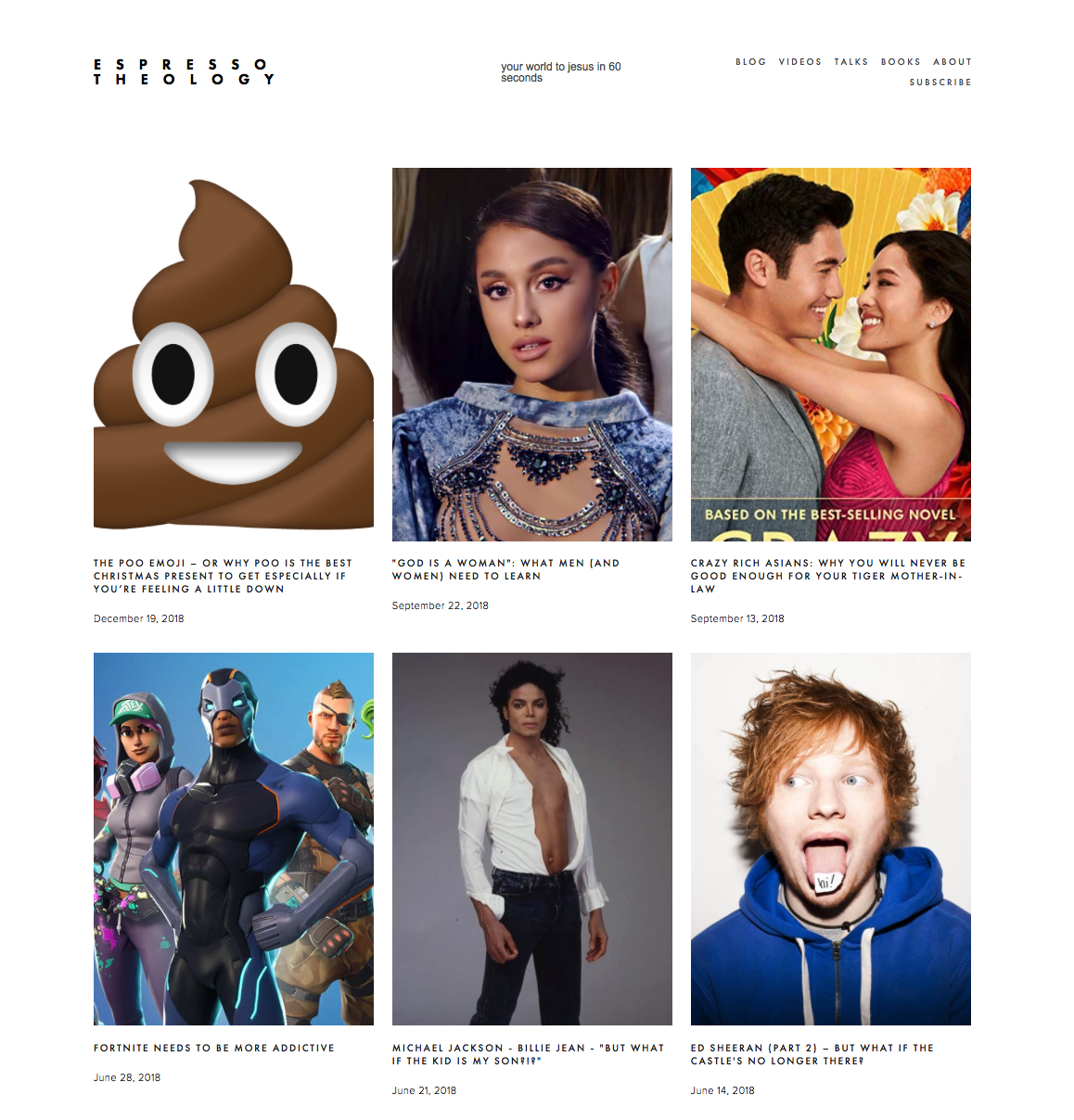

For example, he charts out how “the Bible gives us different ways of explaining sin to different audiences and different people.” Therefore we can “cautiously appropriate the language of brokenness for our evangelism”. This isn’t all we say, but it might be where we begin. He encourages us to evangelise in a way that resonates with our listener’s story, before dismantling the false hopes, and then presenting Christ as the story’s fulfilment. This is what Chan does regularly in his popular blog, Espresso Theology, taking you to the gospel through the lens of a cultural item in 30 seconds. Readers will recognise his approach as very similar to that of Tim Keller or Dan Strange’s model of ‘subversive fulfilment’ (though I wonder if someone like Strange has a clearer emphasis on the confrontation of the gospel).

You Gospel The Way You Were Gospelled

One of Chan’s observations is that we largely evangelise the way that we were evangelised. We get used to one style or one outline and confuse these with the gospel itself, unconsciously privileging one approach over others. Chan’s background is Sydney evangelicalism, and so he takes time to analyse a number of popular gospel outlines, including Two Ways to Live and Bridge to Life. Some of the critique is a helpful reminder that every outline will inevitably miss things out, and therefore we’d do well to consider how these absences may lead to ‘imbalance’ or just how they may be perceived – particularly as culture changes.

Evangelicals have always highly valued the notion of propositional truth. The question we face is how we communicate such truth in a culture that appears to prize feeling over fact. One approach Chan commends is to use the lens of story. Chan is not the first to point this out – and he acknowledges that he is largely borrowing from the work of cross-cultural missiologists. It’s also something that was picked up in 2017’s Evangelism Conference: A Better Story, and the popular Life Explored resource.

Those familiar with Keller will recognise Chan’s focus on plausibility structures (the “accepted beliefs, convictions, and understandings that either green-light truth-claims as plausible or red-light them as implausible”) and the way in which these are subconsciously shaped by community, experience and evidence. Being aware of these will help us ‘know the ocean’ that we and our audiences swims in. This ‘contextualisation conversation’ has been played out in the context of British evangelicalism elsewhere. Chan also weaves in an interesting and perceptive emphasis on hospitality and community, not dissimilar to Ed Shaw’s book, The Plausibility Problem. None of this is a framed as a ‘silver bullet’ – just as ‘just preaching the word’ can’t be seen as magic either. Instead, we’re to be dependent on the Spirit of God working through the gospel, but proactive in how we articulate and apply that gospel.

The Place of Speech-Act Theory

Part of Chan’s argument is based on his PhD thesis on speech-act theory (published here), where he argues that ‘word of God’ in the New Testament can be legitimately read to mean the apostolic gospel message, rather than the canon of Scripture as it had then been received. Without having read Chan’s earlier work, the likes of 2 Thessalonians 2:13 would support his argument – and he’s certainly not the first to make this point (see Bullinger in the Second Helvetic Confession). The significance of this point for Evangelism in a Sceptical World is that Chan argues that to ‘preach the gospel’ is something we can therefore do “in expository or topical form,” as the word of God [i.e. the gospel] is still being proclaimed. The ‘speech act’ is therefore located in the preaching of thegospel: “Topical preaching, as well as expository preaching, can both perform the speech act of the gospel. If the locution is the gospel message, and it is accompanied by the apposite illocutionary force, then Christ crucified has been preached.” There will be consequences to locating the desired speech act in something determined by the evangelist, rather than in the authorial intent of Scripture (however one understands that!), but hopefully our gospel ‘illocution’ (i.e. the desired or directed response) is still in some way determined by a set of illocutions given by God in Scripture.

Food for Thought

Like most books, there will be quibbles to push back on. There are evidently vexations residing within reformed evangelicalism that Chan feels work against effective evangelism. To my ears, sometimes these felt over-egged, but then again I’m inhabiting a different context to the author. Take for example his critique of the ‘traditional expository Bible talk’, which he describes as “a product of Western, logical, linear, Enlightenment and inductive communication”. As one pastor-theologian pointed out to me, what one understands as ‘traditional’ here will inevitably vary. I would argue that the principle of exposition as ‘saying what’s in the Bible’ is something that is of inestimable and timeless value to the church, and yet inevitably our different subcultures of evangelical Christianity will sculpt out their own versions of what this ‘traditionally’ ends up looking like. It’s some of the latter that I think Chan has a problem with – and so to be challenged as to whether our ‘normal practice’ is actually ‘best practice’ for our cultural milieu is fair critique.

A Comprehensive Companion for Mission

This is a rich and stimulating tome, and its textbook format makes it a handy and comprehensive tool. I put it straight on the reading list of a Mission & Apologetics module I’ve been involved in. Some of the later chapters are particularly practical, including those on talk preparation and story-telling – and Chan even includes a useful list of questions to ask a bride and groom to give an evangelistic wedding sermon.

The critique the book is likely to get is that Chan steers too close to making the gospel palatable, not simply understandable. I’m not convinced he is guilty of this, but then again we do want people to see Christ as glorious and attractive. Our reformed evangelical inclination probably is to under-adapt, and just ‘stick to the gospel’. As Don Carson says, “the gospel is still the power of God that brings salvation, and Sam helps us recover that confidence.” I remember hearing UCCF’s Richard Cunningham say that good apologetics will make the offence of the cross more obvious, not less, and I think Chan gets this right. Whilst holding to reformed evangelical convictions, Evangelism in a Sceptical World invites us to engage with questions we might not otherwise face up to. And ultimately Chan does so for the sake of the lost, for which he should be commended.

Pick up Evangelism in a Sceptical World here. Zondervan have also created an accompanying video series featuring Chan.

–

You can watch Chan get interviewed by Aussie pastor Dominic Steele here. Just as Chan isn’t afraid to raise big questions, Steele isn’t afraid to question some of Chan’s ideas. The two discuss whether or not the book’s approach ’empties the cross of its power’, and whether an over-emphasis on engaging with shame could undermine the biblical notion of guilt and atonement. I was encouraged by the conversation.

–

Disclaimer: I received a free copy of this book from the publisher, but I hope this is still a fair review.