A Common Rule by Justin Whitmel Earley – A Review

“Habits form us more than we form them.”

That’s the concern flagged up by Christian, lawyer, and author Justin Whitmel Earley in his challenging book, A Common Rule: Habits of Purpose for an Age of Distraction. It represents an evangelical attempt to engage with Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit and James K. A. Smith’s You Are What You Love and build on the recent trend of rediscovering a Christian ‘rule of life’.

A Conversion Story

Earley begins with a powerful story of his own conversion, but this isn’t a conversion to Christianity. Instead Earley describes how, when working as a lawyer, though he would have identified as a Christian, his body finally became ‘converted’ to the anxiety and busyness that had become is default as he effectively worshipped the idols of his career and lifestyle: “I had said one thing: that God loves me no matter what I do – but my habits said another: that I better keep striving in order to stay loved.” He poignantly puts it like this: “while the house of my life was decorated with Christian content, the architecture of my habits was just like everyone else’s.” This crash led him to consider how he might re-structure his life – and from this arises what he calls ‘the Common Rule’.

The Earley Bird Catches The Worm

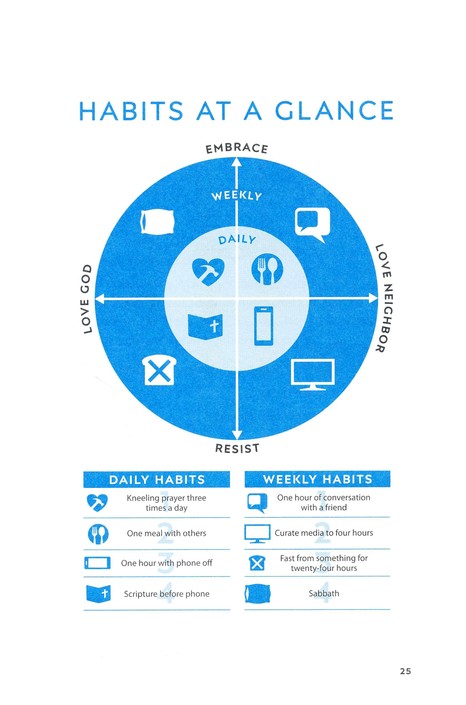

The Common Rule is essentially eight habits, four of these being daily practices and another four weekly. The daily habits are as follows:

- kneeling prayer at morning, midday, and bedtime;

- one meal with others;

- one hour with phone off;

- Scripture before phone in the morning

The weekly habits are:

- one hour of conversation with a friend

- curate media to four hours;

- fast from something for 24 hours;

- sabbath

Earley maps out these eight habits on a set of two axis, with each habit then corresponding to two different emphases. As in the illustration on the right, on one axis you have love of God and love of neighbour, and on the other embrace and resistance. So, for example, the habit of sabbath counts as corresponding to both love of God and embrace, whereas an hour without your phone corresponds to loving neighbour and resistance.

Earley spends a chapter on each of these habits and there’s much that is refreshing, persuasive and inspiring. Generally each one reads as a healthy principle to work from, even if one chooses not to ‘commit’ or implement it in the way Earley suggests. Personally I found his chapter on prayer slightly strange, as if praying was more about me framing my day than about depending upon and asking from God. But there was so much in these eight chapters that was inspiring and challenging and made me want to take hold of my ‘everyday’ and re-think them. Earley is certainly clear that these eight habits are just one option and his goal is less about getting you to sign you up to his ‘Common Rule’, and more to convince you of the need to be intentional about your habits and to commit to them. This leads us into a more significant general conversation about the notion of a ‘rule of life’ and the place of habit in the Christian life, rather than digressing over the specifics of the practices he advocates.

We All Have A Rule of Life

Earley’s argument has two main steps. Firstly, we are creatures of habit. In other words, whether or not we admit it, we all have habits. In fact, mostly we don’t realise we have them. To put it simply, habits are the things we usually do and the ways we normally think; the routines, rhythms and norms that make-up our days. Sometimes these have been chosen by us, but often they’re what we default into, perhaps because we’re imitating others or perhaps because we’re assuming this is the cultural norm: ‘it’s just what we do, right?’. For example, think about what you do when you first wake-up, or when you get in the car, or when you finish work. Think about how you spend your weekends, or your meal-times, or how often you check your phone. These are all habits.

But Earley’s second step is to argue that these habits shape us. Here he is indebted to the work of James K. A. Smith, who has described these habits and patterns of our lives as ‘cultural liturgies’. We often use the language of liturgy for religious acts, perhaps part of a church service, the theory being that religious liturgy helps form us spiritually in one way or another. But Smith argues that all of life is made-up of liturgies, habits that will be silently schooling us in how to live and make sense of the world. In effect, this is an embodied, pre-cognitive formation – and it is to our detriment if we don’t ‘own’ or identify the impact that these lifestyles can have upon us. As Earley puts it:

“By ignoring the ways habits shape us, we’ve assimilated to a hidden rule of life: the American rule of life. This rigorous program of habits forms us in all the anxiety, depression, consumerism, injustice, and vanity that are so typical in the contemporary American life.”

Therefore, whether or not your Christian sub-culture would be predisposed to value the notion of a ‘rule of life’, the point is that we all already have one. According to Earley, the question facing us is not so much whether we each adopt a ‘rule of life’, but whether we’re going to acknowledge the many ways in which we’re already being shaped by our habits. And are we willing to get a hold of these habits and choose differently. For me this is one of the key take-aways from Earley’s book: to be awake to the ways in which my life patterns are forming me – and therefore, in response, to be persuaded to craft my own pattern of living that involves some commitment to ‘habits’.

A Net To Catch Our Days

Earley notes that the first Christian advocates of a ‘rule of life’, the likes of Augustine and Benedict, always had a particular spiritual goal in mind: love. Such rhythms were about taking “the small patterns of life and organising them towards the big goal of life: to love God and neighbour”. Another helpful image that Earley uses for habits is that of gears by which we direct life toward the purpose of love. He also notes that the original use of ‘rule’ in this context came from the Latin regula, which he argues was not so much about a ‘rule book’, i.e. a guilt-inducing set of commands, but rather a bar or trellis that a plant would grow on. In other words, the ‘rule’ provides order for healthy growth, giving it direction so that it does not simply develop in disordered chaos but flourishes. And so, whilst the phrase ‘rule of life’ might carry connotations of a set of laws, the true sense is about being intentional about the trellis our lives flourish on. I’m not going to claim to know whether or not that’s historically legitimate, but obviously there’s a linguistic debate to be had about how helpful it is to continue using the phrase today, given its connotations of law-keeping, but it’s helpful to know the back-story – or at least one take on it.

In that regard, for me, one of the most convicting lines in Earley’s book is this quote from the American author Annie Dillard:

“How we spend our days is, of course, how we spend our lives. What we do with this hour, and that one, is what we are doing. A schedule defends from chaos and whim. It is a net for catching days. It is a scaffolding on which a worker can stand and labour with both hands at sections of time.”

My sense is that this emphasis on intentionality is trending at the moment. Our modern lives are hyper-connected and hyper-busy – many of us experience the sense of being overwhelmed. We do so much by default or because we think we have to. We barely have a moment to catch our breath and think about what we’re doing. But as Earley says, “if you want to get your hands on who you are becoming, you need to get your hands on habits. A rule of life is how we get our hands on our habits.”

Because We’re More Than Brains On Sticks

One of the often-repeated planks of James K. A. Smith’s work is his critique of evangelicalism’s default anthropology of people as simply ‘brains on sticks’, i.e. ‘thinking things’. Smith argues this is a dangerous framework for understanding ourselves, because it wrongly suggests we are simply formed by our reasoned beliefs and through processing propositional information, rather than also by our experiences and practices.

In response, some may argue that emphasising Christian habits may well lead to outward conformity, but it is no guarantee of true inner spiritual transformation. Indeed, Smith has been accused of creating too much of a dichotomy between thinking and doing. Some have even criticised him for advocating a dangerous “pre-reformation religiosity”. Earley’s book may receive similar accusations and questions from some: does it emphasise works at the expense of grace? Can we encourage such habits, whilst also guarding against the seemingly innate desire most of us have to justify ourselves – and thus be guilty of a Pharisaical self-righteousness. Quite how does the gospel, a propositional reality, fits with a set of tangible practices? How do habits ‘inhabit’ truth and gospel proposition?

These questions are hugely important, but it’s worth acknowledging that those of us likely to be asking them probably wouldn’t hasten to previously recognise the negative impact of habits. We know some behaviours are not good for us. And surely the often cited evangelical principle of ‘we become what we worship’ (e.g. Psalm 31:6) can be boiled down to the impact that our habits and priorities have upon us. In this regard it seems we’re prepared to see habits as effecting us negatively (although Earley and Smith would say we’ve probably not grasped just how shaped we have been), but perhaps we’re not as quick to affirm Earley’s emphasis on habits to bring positive transformation. And yet many of us would talk about the importance of certain activities: attending church x amount of times a week; perhaps having a time of daily personal devotional Bible-reading and prayer; being part of a discipleship group. If anything, isn’t this the skeleton of a rule of life? Isn’t this an acknowledgement that we do see some ‘evangelical habits’ as being important?

Habits, Hearts, and the Gospel

To be fair to Smith, he has rejected the idea of liturgical determinism, i.e. the idea that our habits guarantee changed hearts, and he has stated the need for cognitive reflection. Here perhaps we can bring in other voices to help us navigate this area: Tim Keller has sought to synthesise Smith’s work, without disregarding evangelicalism’s traditional emphasis on ‘propositional truth’. Taking us back to Aristotle and Plato, he notes that Plato tended to emphasise how right action follows from right thinking (‘as we think, so we are’), whereas Aristotle tended to emphasise right thinking follows form right action (‘we become what we do’). Keller’s response is as follows:

“Christians should be careful not to lift up either thinking or behaviour as the key… the key is the heart. The heart’s commitments are changed through repentance – which involves both thinking and behaviour.” (see Keller’s footnote 26 in Center Church, p. 219).

In other words, the biblical category of the heart represents the inner person, the essential self, and encapsulates both thinking and feeling (Mark 7:20-23; Luke 6:43-45; Romans 1:21-25; Ephesians 4:17-24; James 4:1-10). Biblically speaking, it is here that belief or unbelief occur, which are not simply terms describing affirmation or denial of propositional statements, but are encapsulating something deeper, something at a heart-level that is intrinsically about worship of God or something else.

It is right to therefore ask in what ways our hearts are being shaped by our practices, for in doing so we “bring them into conformity with the revelation of God in Scripture,” as Matthew Lee Anderson puts it in his book, Earthen Vessels. Anderson is arguing that evangelicals often have a weak theology of the human body, and posits that as a result “we are more susceptible to tacitly adopting secular practices and habits”. Maybe here there is a balancing act between guarding against blind naievity regarding our lifestyles impact upon us, and endless analysing of every everyday act?

Coming back to A Common Rule, Earley advocates for a “gospel-based rule of life”, but I did wonder whether more could have been said up-front to spell this out. He certainly acknowledges that you need both “the right theological truth” and “putting that truth into practice,” but I’d like to see this relationship explored at greater length, particularly in the introductory sections of the book.

Commitments and Failure

Earley ends the book with a striking epilogue, entitled On Failure and Beauty, in which he admits that his own experience of living out his common rule has often been marked by failure. Perhaps a critic would say this admission runs the risk of discrediting the whole book, but on the contrary Earlier argues that it is precisely the point: there is an inherent tension in proposing a set of habits which is that we’ll often fail at them, in turn giving rise to feelings of guilt or even despair. And so the gospel of grace must be bound up in those habits – they must be about not simply ‘the good life’, but ‘the gospel life’. Earley describes defaulting to his habits amidst the failure and seeing the divine beauty to which such habits point our hearts:

“How we deal with failure says volumes about who we really believe we are. Who we really believe God is. When we trip on failure, do we fall into ourselves? Or do we fall into grace?”

It strikes me that intentional Christian habits should provide the opportunity to push the gospel of grace into the cracks and crevices of our hearts, through the cracks and crevices of our lives. As such it needs to be built into these practices that our lives will be marked by failure, weakness and sin. We will inevitably neglect not just our good intentions or a set of personalised commitments, but our God-given calling to love God and love our neighbour. The point is therefore that failure does not have to be an impediment to a life worshipping God, rather “it’s the way to it”. No ‘rule’ can “contain my chaos”, and it is this path of failure that will display the glory of God’s grace. I think I’m reading Earley faithfully here, rather than making assumptions. He sees habits as ‘hooks’ that snag at our lives and re-orientate us to the fundamental truths of what we believe, and ultimately they must be ‘hooks’ for the gospel.

Common Means Together

The significant element of Earley’s proposal that I haven’t yet touched on is that he believes there is great value in such a ‘rule of life’ when it is done together. Hence, a ‘Common’ rule, as in the Book of Common Prayer. These are habits to commit to together. I had a really interesting chat with a friend about this recently. As evangelicals I think we are instinctively hesitant to bind people to a set of practices, because we are wary of creating a legalistic culture. So I imagine it is this element of Earley’s proposal that we will tend to ignore. Yes, consider your own habits and by all means be intentional about your daily rhythms, but the moment we ask others to commit to them feels like we are in danger of the kind of ‘do not touch, do not taste’ culture that the apostle Paul challenged so passionately in his letter to the Colossians. But again, the reality is we do already encourage ‘common practices’ (church; Quiet Time; personal evangelism; giving), so what is different here?

There is another element to this that I don’t recall Earley touching on, but which I think is worth considering in our cultural moment, and this is the missional impact of a ‘rule of life’. Increasingly it will be our distinct Christian lives that will be what people notice and what will draw people towards the gospel or give the gospel a hearing. If our lives are no different, bar the activities we do in private or on Sundays, then we have little chance of this happening. But having daily rhythms where gospel truth is infused and where ‘gospel culture’, to use Ray Ortlund’s phrase, is embodied, means we have everyday opportunities to witness to our God of grace.

How We Spend Our Days Is How We Spend Our Lives

What Smith and now Earley have advocated for is a “counterformation” to the rival habits and patterns that we can passively fall into. To say that we don’t need to cultivate such habits or routines is to miss the point that we already have habits and routines. And, as Earley says, “that usually means someone else has chosen those habits for us – and usually that someone doesn’t have our best interests in mind.”

Here Earley puts his finger on something crucial for real-world disciples to understand: “what we so often overlook in our abstract hunt for beautiful lives is the striking plainness of the moments that make up the days that make up our lives”. It is the everyday moments of our lives that connect the ordinary to the extraordinary, a whole life lived in worship of the triune God. If this is true, why do we hesitate to consider how our everyday lives might be filled with gospel-infused rhythms? Earley again puts it well: “We will never build lives of love out of anything except ordinary days – simple, extraordinary beautiful, but still ordinary days.”

A Common Rule has challenged me: first, to consider how my ordinary days might be forming me in ways I hadn’t grasped; and then, second, to take hold of these ordinary moments and find ways to get the gospel into the ‘nooks and crannies’ of my life. I’ve not read many books quite like it – it’s made me think hard about my own life. And whilst I would like him to be more explicit in places, I’m very grateful for Earley having written it.

You can pick up a copy of A Common Rule here.

Disclaimer: I received a review copy of the book, but I hope this is still an impartial and fair review.